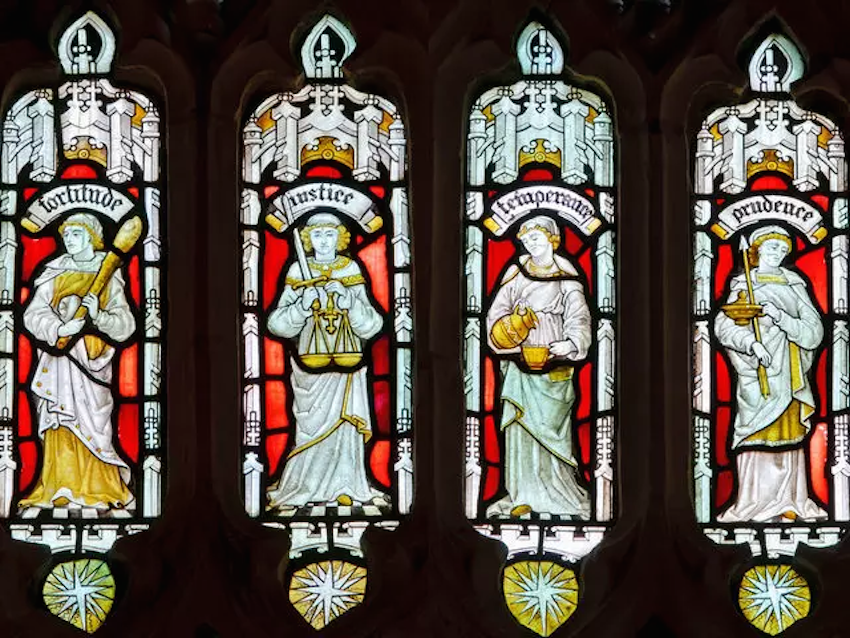

In today’s episode, we revisit some of the material covered in the previous chapter. In this episode, C.S. Lewis re-examines the question of morality through the classical lens of the four Cardinal Virtues: Prudence, Temperance, Justice, and Fortitude.

S1E14: “The Cardinal Virtues” (Download)

If you enjoy this episode, please subscribe on your preferred podcast platform, such as iTunes, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Audible, and many others…

For information about our schedule, please see the our Roadmap for Season 7.

Finally, if you’d like to support us and get fantastic gifts such as access to our Pints With Jack Slack channel and branded pint glasses, please join us on Patreon for as little as $2 a month.

Show Notes

Introduction

- Matt hijacked the start of this episode by naming some of the books they use to elevate his microphone:

○ “Hymns and Homilies of St. Ephraim”

○ “A Summa of the Summa” by Peter Kreeft

○ “Mary and the Fathers of the Church” by Luigi Gambero

○ “The King James Only Controversy” by James White

○ “How to do Apologetics” by Patrick Madrid

- According to Matt, this explains why David’s ideal woman is Amy Farrah Fowler!

- While discussing David’s reading habits, he mentioned that he’s a fan of the Pints with Aquinas podcast by Matt Fradd, who is author of several books including the “The Porn Myth”.

Quote-of-the-Week

Courage is not simply one of the virtues, but the form of every virtue at the testing point.

C. S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters

Toast

- The Beer-of-the-week was, once again, Franziskaner.

Discussion

01. “The Seven Virtues”

- Jack begins by explaining that he had to get to the point quickly in the previous chapter, because it was a talk given on air. In writing, he can now tackle the subject of morality with a more classical approach.

- There are seven virtues which Jack identifies. There are three theological virtues: faith, hope and love. There are also four Cardinal Virtues: Prudence, Temperance, Justice and Fortitude.

According to this longer scheme there are seven ‘virtues’. Four of them are called ‘Cardinal virtues, and the remaining three are called ‘Theological’ virtues. The Cardinal’ ones are those which all civilised people recognise: the ‘Theological are those which, as a rule, only Christians know about.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- Lewis gives a definition for the word “cardinal”.

[Cardinal] comes from a Latin word meaning ‘the hinge of a door’. These were called ‘cardinal virtues because they are, as we should say, ‘pivotal’.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- David was surprised that Jack never actually defines “virtue”. Etymologically, it comes from the Latin word “virtus” which, in turn, comes from the Latin word “vir”, which means “man”. His education in the virtues has primarily come through The Catholic Man Show podcast. Here are some of their episodes on the subject of virtue:

○ Episode #84: Patience

○ Episode #82: Courage

○ Episode #77: Natural & Supernatural Virtue

○ Episode #48: Talking Virtue in Bartlesville

○ …

- For a working definition of “virtue”, David went to St. Thomas Aquinas, the medieval scholastic who drew heavily from the works of Aristotle. He defines virtue as:

…good qualities of mind whereby we live righteously. (ST IaIIae 55.4).

St. Thomas Aquinas, ST Iallae 55.4

- In other words, virtues are good habits, vices are bad habits.

- What are the virtues?

1. Prudence

Prudence means practical common sense, taking the troule to think out what you are doing and what is likely to come of it.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- Prudence is the virtue that directs all the others. But as Jack points out, most people don’t often think of prudence as a virtue.

Nowadays most people hardly think of Prudence as one of the ‘virtues’. in fact, because Christ said we could only get into His world by being like children, many Christians have the idea that, provided you are ‘good’, it does not matter being a fool.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- This is a reference to Matthew 18:3, where Jesus tells us to “become as little children”.

- Lewis points out that most children are sensible.

Most children show plenty of ‘prudence’ about doing the things they are really interested in, and think them out quite sensibly.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- Lewis points out that Christ wants both our hearts and our minds.

As St Paul points out, Christ never meant that we were to remain children in intelligence: on the contrary. He told us to be not only ‘as harmless as doves’, but also ‘as wise as serpents’. He wants a child’s heart, but a grown-up’s head. He wants us to be simple, single-minded, affectionate, and teachable, as good children are; but He also wants every bit of intelligence we have to be alert at its job, and in first-class fighting trim.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- To help understand this saying of Jesus, David gave the analogy of a little child jumping into her father’s arms.

- What if we do not consider ourselves to be “intellectuals”? Here’s what Lewis had to say…

It is, of course, quite true that God will not love you any the less, or have less use for you, if you happen to have been born with a very second-rate brain. He has room for people with very little sense, but He wants everyone to use what sense they have.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

David followed up with some thoughts about great Saints of the Church who were considered by their contemporaries to be simple or unextraordinary. Some of the people he had in mind here were St. Therese of Lisieux, Brother Lawrence, and St. John Vianney.

02. “Learning to Swim”

God is no fonder of intellectual slackers than of any other slackers. If you are thinking of becoming a Christian, I warn you, you are embarking on something which is going to take the whole of you, brains and all.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- Jack points out that Christianity is an education in itself.

Anyone who is honestly trying to be a Christian will soon find his intelligence being sharpened: one of the reasons why it needs no special education to be a Christian is that Christianity is an education itself. This is why an uneducated believer like Bunyan was able to write a book that has astonished the whole world.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- The book that Jack referenced here was John Bunyan’s “The Pilgrim’s Progress”.

- David referenced a story by Boston College Philosophy Professor, Peter Kreeft. He divides his students into theists and atheists, then has them take the opposite view and make the case for this view. The believers, posing as atheists, always come out with the stronger case. Christians wrestle with these questions on a regular basis.

03. “Temperance”

- The second virtue is…

2. Temperance

Temperance doesn’t necessarily mean abstention and it also doesn’t refer only to alcoholic drink. Temperance just means taking a pleasure to the right level.

Temperance is, unfortunately, one of those words that has changed its meaning. It now usually means teetotalism. But in the days when the second Cardinal virtue was christened ‘Temperance’, it meant nothing of the sort. Temperance referred not specifically to drink, but to all pleasures; and it meant not abstaining, but going the right length and no further.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- Lewis points out that the true teetotalist religion is Islam. Mormonism might also be classified this way.

It is a mistake to think that Christians ought all to be teetotallers; Mohammedanism, not Christianity, is the teetotal religion.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

Wherever the Catholic sun doth shine, there’s always laughter and good red wine. At least I’ve always found it so. Benedicamus Domino! [Let us bless the Lord]

Hilaire Belloc

In Catholicism, the pint, the pipe, and the cross can all fit together.

G. K. Chesterton

- Lewis is saying in this passage that Christians can partake in good things – alcohol, money, and sex to name a few – but not in a disordered way, or by having too much of it. Then these things turn to debauchery (drunkenness), greed, and unchastity. The point is that the thing is not bad in and of itself.

An individual Christian may see fit to give up all sorts of things for special reasons – marriage, or meat, or beer, or the cinema; but the moment he starts saying the things are bad in themselves, or looking down his nose at other people who do use them, he has taken a wrong turning.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- At the time of recording, Byzantine Catholics like David (as well as Eastern Orthodox) were in the Nativity Fast, which means that they give up good things (like meat and dairy) as a penitential practice.

- David and Matt discussed chastity and sex. Matt explained that he typically describes Catholic teaching to people primarily in terms of natural reason since, after all, Christianity provides a guide for the correct functioning of the “human machine”.

- People can be intemperate about lots of things other than alcohol. Are you temperate with regards to Netflix?!

It helps people to forget that you can be just as intemperate about lots of other things. A man who makes his golf or his motor-bicycle the centre of his life, or a woman who devotes all her thoughts to clothes or bridge or her dog, is being just as ‘intemperate’ as someone who gets drunk every evening. Of course, it does not show on the outside so easily … but God is not deceived by externals.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- Why do David and Matt drink on the show? In explaining this, once again, David stole liberally from The Catholic Man Show, since the hosts also drink on air and regularly address this issue. Matt and David share a beer because God made the things of this world good (see Genesis 1:31). We can give glory to God by consuming the good things of this world which He made for us, but only as long as we consume them to the right degree (i.e. with temperance). For those suffering from alcoholism, the “right degree” is probably complete abstinence. For those dealing with addictions and their families, David would recommend a book recently released by his friend Scott Weeman, “The Twelve Steps and the Sacraments”.

03. “Justice”

3. Justice

- Lewis explains that justice is really “fairness”.

Justice means much more than the sort of thing that goes on in law courts. It is the old name for everything we should now call ‘fairness’; it includes honestly, give and take, truthfulness, keeping promises, and all that side of life.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- Matt offered a caution from Lewis’ book “The Great Divorce” about giving someone “their due”.

4. Fortitude

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

Fortitude includes both kinds of courage – the kind that faces danger as well as the kind that ‘sticks it’ under pain. ‘Guts’ is perhaps the nearest modern English. You will notice, of course, that you cannot practise any of the other virtues very long without bringing this one into play.

- David told the story about the song The Altar and the Door by Casting Crowns. He heard the lead singer explain the story behind the song and album and how, when our fortitude fades, black and white turn to grey and we begin to negotiate with sin.

04. “Virtue vs. Character”

- Finally, Jack explains the difference between virtuous acts and virtuous character. He gives the analogy of a tennis player:

Someone who is not a good tennis player may now and then make a good shot. What you mean by a good player is a man whose eye and muscles and nerves have been so trained by making innumerable good shots that they can now be relied on … In the same way a man who preservers in doing just actions gets in the end a certain quality of character. Now it is that quality rather than the particular actions which we mean when we talk of a ‘virtue’.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- Jack explains that the distinction between acts and character is very important. If we focus on the former, we will reach the following incorrect conclusions:

1. The “how” and the “why” don’t matter

- Right actions done for the wrong reasons don’t build character and it’s character that we want!

We might think that, provided you did the right thing, it did not matter how or why you did it – whether you did it willingly or unwillingly, sulkily or cheerfully, through fear of public opinion or for its own sake. But the truth is that right actions done for the wrong reason do not help to build the internal quality or character called a ‘virtue’, and it is this quality or character that really matters.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- David disagreed with Lewis’ assessment a bit. Right actions done for the wrong reasons can be a starting point for us. In being virtuous, we can see the beauty of virtue and see that this is indeed the right way to run the “human machine”. Jack will actually build on this idea himself in Book IV’s chapter “Let’s Pretend”.

2. God cares most about “the rules”

- This is incorrect. What God most cares about is transforming us, so that we want to love Him!

We might think that God wanted simply obedience to a set of rules: whereas He really wants people of a particular sort.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

05. “

3. Virtue is only for earth, not Heaven

- Virtue is the very thing which will allow us to enjoy Heaven!

Now it is quite true that there will probably be no occasion for just or courageous acts int he next world, but there will be every occasion for being the sort of people that we can become only as the result of doing such acts here … if people have not got at least the beginnings of those qualities inside them, then no possible external conditions could make a ‘Heaven’ for them – that is, could make them happy with the deep, strong, unshakable kind of happiness God intends for us.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, The ‘Cardinal Virtues’

- At the end, David mentioned Sarah Swafford’s talk on “emotional virtue” on Leah Darrow‘s podcast, Do Something Beautiful.

Wrap Up

Concluding Thoughts

Support Us!

• The outline for this chapter is available here.

You mentioned In “PWJ: S1E14 – MC B3C2 – “THE CARDINAL VIRTUES” Lewis’ definition of Justice.

I like what he says, “It is the old name for everything we should now call fairness. It includes honestly, truthfulness, and all that side of life.”

Perhaps I am a little presumptuous, but I wonder if the idea of “fairness” degrades justice.

Fairness to me means, ” render to every man according to his deeds” (Romans 2:6 kjv)

but God’s Justice, which seems to me the kind of justice we ought to emulate, is the Justice of “making things right again”.

In this episode you both seem to struggling back and forth and you mention the scene in The Great Divorce and this is what I think is the central point of contention.

We think of Justice as fairness, get what you “deserve”, but I think as Christians we must say that we deserve nothing. Everything we have is a gift of grace. Even in repentance the prospect of “getting what we deserve” is frightening to me. Instead I rely on God’s Justice, His “putting me right” and His Mercy is His Justice even when I don’t deserve it.

Does this make sense? I’m sort of thinking out loud.

I’m looking to be scrutinized or challenged or corrected.

I feel like these thoughts are consistent with the Church Fathers, but to be honest I’m unable to quote them off the top of my head.

Anyways, I love the podcast, I just started season 1 after I listened to “The Great Divorce” and my love for C. S. Lewis was rekindled.

I really look forward to listening to the rest.

God bless,

Mark

Hey Mark,

Thanks for your thoughts. I’m not completely sure if we can describe God’s justice as being different from the classical virtue of justice. I’d rather say that His justice is complemented by His perfect charity and this results in us describing his character as being that of one who seeks to make things right again. Likewise, I would say that we rely upon God’s grace rather than His justice. His justice is unflinching (like the Moral Law and the Times Tables), but His love is what makes our righteousness possible.

Likewise, I’m not sure if it’s fair to say that as Christians we must say that we deserve strictly nothing. For example, parents deserve obedience of their children and a worker deserves his wage. I do, however, think it’s fair to say that we don’t deserve anything from God. As you say, we receive everything as gift, beautifully illustrated in Lewis’ analogy of the child who asks his father for sixpence in order to buy him a present!

Keep the feedback coming!

God bless,

David.

Hey David,

Thanks for replying so quickly.

I think I got sidetracked, this chapter is about how we practice justice and I suppose the ideas of fairness and honesty are the point here

I suppose I started talking about the Justice of God because it’s something I struggle with. How is God perfectly Just and Merciful? I know nothing of the classical definition of virtue of justice, is this definition consistent with who God Is?

This seems to be tied up in the theology of the Incarnation, Cross and Resurrection, so maybe it’s best I don’t make any more assumptions 😊

As for the whole “we deserve nothing bit”, I agree we don’t “deserve” anything from God. But it seems to me the examples you give are less a matter of deserving and more a matter of sin.

Obedience to parents is a command and getting paid for your labour is about fairness (justice?? 😉)

I personally don’t think this is as depressing as it may initially sound to people. I think it’s actually freeing, to accept situations as they are and to trust in God to work good through them.

Looking forward to your response,

Mark

You’re welcome 🙂

It’s a necessary part of His nature, since He is goodness itself. He’s perfectly justice and perfectly merciful. These intersect at the cross where both justice and mercy are satisfied.

Yup.

I think that we have responsibilities to each other due to the nature of our relationships. Children are owed care from their parents etc.

Pingback: CPS – Livro III: Cap 2 – Cartas de Narnia