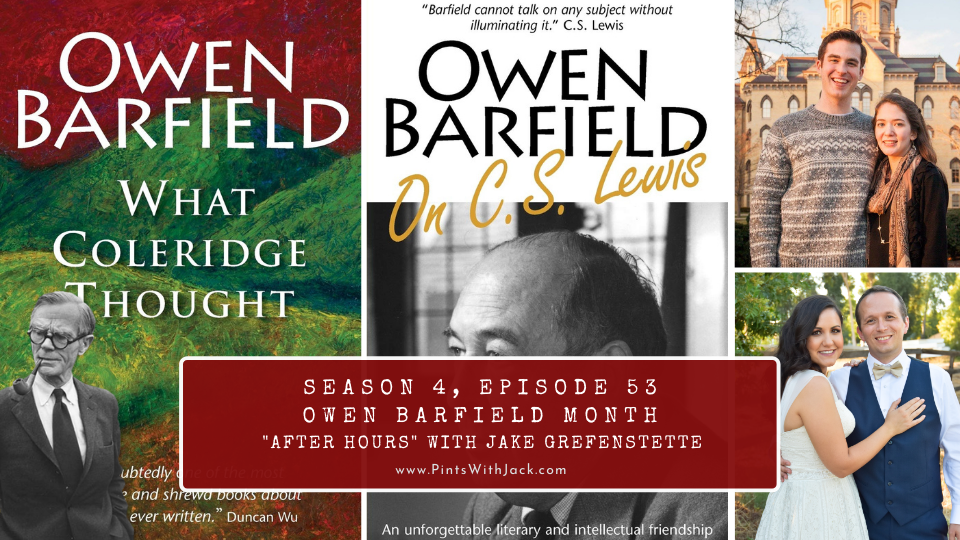

Today we continue “Barfield Month” by talking to Jake Grefensette about the literature and poetry of Owen Barfield.

S4E53: “After Hours” with Jake Grefenstette (Download)

If you enjoy this episode, you can subscribe manually, or any place where good podcasts can be found (iTunes, Google Play, Amazon, Podbean, Stitcher, TuneIn and Overcast), as well as on YouTube. The roadmap for Season 4 is available here.

More information about us can be found on our website, PintsWithJack.com. If you’d like to support us and get fantastic gifts, please join us on Patreon.

Timestamps

00:00 – Entering “The Eagle & Child”…

00:11 – Welcome 00:39 – Jake Grefenstette

03:39 – Quote-of-the-week

03:58 – Drink-of-the-week

04:48 – Discussion: Finding the Inklings and Barfield

06:10 – Discussion: Barfield’s attraction

08:07 – Discussion: Barfield’s critical works

16:27 – Discussion: Barfield’s creative works

26:12 – Discussion: Barfield’s poetry

32:26 – Discussion: Barfield for Lewis fans

34:42 – “Last Call” Bell and Closing Thoughts

YouTube Version

After Show Skype Session

No Skype Session today!

Show Notes

Biography

Originally from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Jake Grefenstette has studied theology, philosophy, and literature at the Universities of Notre Dame, Chicago, Beijing, Oxford, and now Cambridge, where he is working towards his PhD as a member of King’s College. At Cambridge, Jake studies the legacy of Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 20th century thinkers like Owen Barfield, working at the intersection of theology and literature. Jake is also interested in the broader legacy of the Romantic tradition in Chinese poets like Xu Zhimo, Hai Zi, and Xi Chuan. Outside of his thesis, Jake is involved in the study and practice of film, evening holding a “special thanks” film credit on the extended cut of The Tree of Life. During his free time in Cambridge, he shoots and develops expired film stocks with his wife, Cristina. Nearly all photographic efforts spotlight their dog, Frodo Waggins.

Biographical information for Jake Grefenstette

Chit Chat

- Jake mentioned that he recently looked at some Chinese translations of Lewis works – The Screwtape L is “Dìyùlái hóng,” or “Letters from Hell.” All of the translated titles are all amazing.

- Jake’s name was given to me by the first guest on Barfield Month, the Inkling’s grandson, but when I sent my co-hosts the outline for the month, Matt Bush told me that he knew Jake. Cristina, his wife, worked with Matt in a student business organization at Notre Dame and took over Matt’s role after he graduated. Jake also followed in Matt’s footsteps in doing Notre Dame’s year abroad at Oxford.

- Jake managed to get a “Special Thanks” on the movie, The Tree of Life? He had always loved Terry’s work and was in Austin one summer working on a short film with one of his editors and had the opportunity to offer some notes on some extended cut edits.

Quote-of-the-week

- The quote-of-the-week is probably one of my favourite quotations of Barfield’s, coming from History In English Words:

“There is no surer or more illuminating way of reading a man’s character, and perhaps a little of his past history, than by observing the contexts in which he prefers to use certain words.”

Owen Barfield, History In English Words

Drink-of-the-week

- It’s early in the morning and I’m going to my godson’s baptism in a couple of hours so the drink-of-the-week isn’t too exciting – I’m having some chrysanthemum tea…

- Since it was 5pm in Cambridge, Jake was drinking some Bushmill’s tea, as a nod to Lewis’s Northern Irish roots.

Discussion

Background

- Jake grew up in a Catholic household, where Lewis and Tolkein were bookshelf staples. His first serious introduction to Barfield was over pints with some friends at the Eagle & Child pub! He kept up an interest in him for a few years, but it’s really been at Cambridge (“the other place”) that he’s been able to do more focused work, where Barfield has garnered a pretty sizable following.

- Poetic Diction was the text that really caught Jake’s attention. Although Barfield really isn’t on the radar of most practitioners of “theology and literature”, he clearly has a lot to bring to the conversation, and he seems only just on the cusp of gaining its due recognition.

- In the first week of Barfield Month, Barfield’s grandson gave us a very broad overview of his grandfather’s life and works. In today’s episode Jake gives us a more detailed survey of Barfield’s writings. A more complete survey of Barfield’s works are accessible at OwenBarfield.org.

Literature

Critical/Philosophical Works

- Poetic Diction. was published in 1928, this is chronologically Barfield’s third book, but the bulk of it was written earlier during his studies at Oxford.

- It’s a remarkable text which stages an innovative history of metaphor and poetic language.

- One of the things he speaks about is a “fallacy” in linguistics that sees language as becoming increasingly metaphorical/poetrical over time. In contrast, when Barfield describes Homer’s works, he speaks of a “meaning still suffused with myth,” with “Nature all alive in the thinking”, such that “the gods are never far below the surface of Homer’s language.”

- Hugely impactful for Lewis (and, perhaps to a less obvious extent, Tolkein) as well as some other important players in 20th century literary theory. There’s a story that Lewis would quote Poetic Diction at Oxford so frequently that it became a joke amongst his students, and apparently many of these students held that Owen Barfield was “simply a name invented by Lewis when he wanted to put forward some idea he didn’t want to take full responsibility for”.

- In Poetic Diction, Barfield speaks of a regrettable lack of what he calls a poetic history of mankind, which he seeks to deliver in 1926 with History in English Words.

- It’s a daring and experimental text which attempts just what it says: to trace English history through words back through Germanic and Greek and Latin and Sanskrit to a theoretical Indo-European language in order to speculate about history and the history of human consciousness.

- Barfield hedges upfront his position as being wholly contingent on the state of contemporary philology, he’s nevertheless willing to draw out some fascinating and daring implications about philosophy and religion generally.

- Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry was published in 1957, which many — including Barfield himself — consider his great mature work.

- This may be a worthwhile read for anyone interested in Lewis’s The Discarded Image.

- Speaker’s Meaning in 1967 distills and develops key ideas from Poetic Diction and History and English Words.

- What Coleridge Thought is published in 1971, which is a central piece of Jake’s thesis at Cambridge.

- Barfield’s reading of Coleridge is unique and sort of radical, but Jake appreciates the way Barfield takes Coleridge seriously as a Christian poet who thinks theologically through literature. This is in opposition to histories of reading Coleridge as a failed poet, or a self-repressive, heterodox pantheist who peppers Christianity into his verse only as a means of “toadying to orthodoxy”. This book has been influential for some great modern readers of Coleridge, most notably, Malcolm Guite.

- Also important in this category of work are are Romanticism Comes of Age (1944), and The Rediscovery of Meaning (1977), two great collections of his essays.

- Jake also made mention of a number of private letters and essays exchanged with Lewis which constitute a debate over meaning, truth, and the imagination they refer to (fondly) as “The Great War.”

Imaginative Works

- The Silver Trumpet (1925) was, in many ways, the first fantastical effort by an Inkling.

- Hugely popular with Lewis, Tolkein, and their children. So obviously of immense historical importance.

- Jake noted that the physical text of the titular trumpet is printed as if it were dancing about the page, reminding us of some of the structural innovations of EE Cummings or Apollinaire.

- Two years later, Barfield turned from fantasy to English People, his serious novel project. Barfield wrote to Lewis about this text in 1927, saying “I need your prayers just now. I have embarked on a really long and complicated novel.” Parts of the original manuscript are now lost, and the book still awaits proper publication, but Jake predicts an increase in interest in this book in years to come.

- Barfield’s writing slowed for a few years as he began his career as a solicitor in London, so the next important text was his verse drama Orpheus (1937; first performed 1948; published 1983), an adaptation of the great classic.

- Orpheus is one of the most adapted stories in history, but what’s interesting about Barfield’s version is the way in which the character of Orpheus is conflated with Barfield’s principal influences from English literature. Speaking at once to a diegetic audience of animals (as well, of course, to the literal audience), Orpheus sings, “Dear friends, who come to help me ease my pain / WIth your presence! Say, what can I do? You have saved me from madness… They cannot answer me–save with my voice. It is their bridge. I will sing to them again.” This scene and (we might say) its metatheatrical puns which Jake thinks interestingly invokes characters like Shakespeare’s Prospero (specifically his speech at the end of The Tempest) as well as Coleridge’s Mariner, who finds himself likewise impelled to repeat his tale.

- One of Jake’s personal favorite collection of Barfield writing is referred to as the “Burgeon Trilogy”: This Ever Diverse Pair in 1950, followed by Worlds Apart and Unancestral Voice.

- These were all written during (and indeed often about) his experience as a solicitor in London.

- The main character is described as aesthetically (though not necessarily psychologically) schizophrenic: his mind is split between “Burgeon,” the creative force, and “Burden,” who deals with the Kafka-esque absurdities and mundanities of modern life.

- This is simultaneously a critique of modern society as well as a (very literal) staging of Coleridge’s distinction between imagination and fancy. For Lewis fans, I think Ever Diverse Pair is the book to read. There’s a whole chapter dedicated to a real life exchange with Lewis.

- Then there’s Night Operation (1975; 2008), Barfield’s sci-fi work, which will be a great read for a post-pandemic world.

- I commented that when my wife and I met the grandson, Owen A. Barfield, last time we were back in England, he gave us a copy of Eager Spring. We both loved the writing, but it did seem like a couple of different books stuck together, with a bunch of pages shameless plugging Anthroposophy stuffed in the middle.

- Jake commented that the tendentious criticism is a common one. He suggested that the sense of stylistic or thematic fracture is something intentional in Barfield, having do with the kind of modern aesthetic “schizophrenia” he describes and stages in works like This Ever Diverse Pair.

Poetry

- Until I began preparing for this season, I hadn’t realized that Barfield was a poet… which I realize was a bit dumb, particularly considering my knowledge of the Inklings and the proclivities of all Barfield’s friends… Jake said that my not knowing about his poetry is a reflection of a relatively meager publication history. Luckily, the history of Barfield’s lack of poetic publications is itself fascinating, mostly because the editors who rejected his work were important figures in their own right.

- Barfield’s submission of some early poetry (from 1920s, among them his long poem The Tower) to Criterion, which was received and rejected by T.S. Eliot. The criticisms Eliot sends back to Barfield about his poems are vague: “I do not feel that you have quite reached the necessary point, though I hardly know why.” Later in his life, reflecting on this editorial rejection, Eliot says he considered Owen Barfield an artist “too valuable to let go,” a poet destined to “make his mark in the long run,” and yet, speaking in an editorial capacity, “difficult to sell.”

- But Eliot’s prediction about making his (poetic) mark in the long run is really finally coming to term. Parlor Press in the US has just published an exciting volume featuring the long poem The Tower alongside other poems and plays. The volume’s introduction features, among other resources, a great survey of Lewis’s varying attitudes towards Barfield’s poetry.

- But perhaps most exciting for your purposes is the Narnian language that shoots through a lot of his poems. In most cases, this seems to be cases of Lewis influencing Barfield; in other cases, as with his “Big Bannister” character, we have evidence of Barfield inspiring Lewis (materialized in that instance as the name of a student in The Silver Chair). Jake read a quick snippet of The Tower that I think you’ll find exciting. The relationship to Lewis is transparent. This passage is early in the poem; it takes the form of an ekphrasis of an imaginary tapestry. Here it is:

…two children

Were out in a wide city, when the snow,

Already fallen, made the dark night blench

And, falling still, caressed them with shy touches,

Until they, wandering onward hopelessly,

Came to a Lion figured huge in stone

And entered magically a carven throat

Found red and warm inside, and soft with life—

Then, by mysterious inward climbings, were

High on the narrow plinth that topped the column

Above their Lion, and among chill stars

Sailing the sky in a perilous barque of stone

Steered by a statue. . . . But the years had lent

Interior meaning to those baby pictures,

The white snow, the red gorge, the chiselled stone,

And the straight column tapering in the dark.

Owen Barfield, The Tower

- I’ve heard Macolm Guite say that C.S. Lewis, when writing poetry, comes off very Barfieldian, citing The Adam At Night, describing an unfallen Adam during the night, alluding to the Original Participation.